History of Lord Hill

Rowland Hill was born at Prees Hall in North Shropshire on 11 August 1772, the fourth of 16 children, and baptised on 16 September in the parish church opposite the Hall.

Sent to school in Chester, where he suffered indifferent health, he gained a reputation for showing kindness to the younger boys arriving at the school. In 1790, approaching the age of 18, Rowland received a letter from his father, John, indicating that his parents thought a career in law would be suitable for him. He responded immediately that he felt he would cut no figure in law, but wished to become a soldier.

His father acquiesced and purchased a commission for Rowland. He also, importantly, urged him to get leave to go to the military academy in Strasbourg so that he could receive formal military training. This was unusual for young British officers at the time, but the experience proved to be of great value to Rowland, who, in 1791, enjoyed two brief periods at the academy before the increasing dangers of the French Revolution caused his uncle Sir Richard Hill, who was returning from Italy to England, to come to Strasbourg to bring his nephew home.

At the age of 21 Captain Rowland Hill saw action at Toulon on the south coast of France late in 1793. A British force had landed to support the people of Toulon against the Republican government in Paris. In December the expeditionary force was compelled to withdraw by the success of the republican troops led by Napoleon Bonaparte. The British General O’Hara was taken prisoner. He and Hill were good friends and O’Hara stated of Hill that “that young man will rise to be one of the first soldiers of the age”.

Hill was present at the Battle of Aboukir Bay in 1801, leading to the departure of the French army from Egypt, and subsequently was involved in defence duties in Ireland and elsewhere in the following six years. It was in 1808, when the Spanish rose up against the French invasion of their country, that the Peninsular War commenced which saw Generals Wellington and Hill working together with ever -increasing trust and effectiveness.

This portrait of Lord Hill by Sir William Beechey, is shown here by courtesy of Shropshire Museums Service. This was the Major-General who, aged 35, landed with a small army in Portugal in July 1808 under Wellesley’s overall command. The British quickly defeated Marshal Junot’s army at Rolica and Vimeiro and the French, by the terms of the Convention of Cintra, were allowed to return to France – in British ships! It was at Rolica that Rifleman Harris observed Hill calmly, under intense fire, steadying his troops and leading them into a successful charge against the French. “It seemed to me that few men could have conducted the business with more coolness and quietude of manner, under such a storm of balls as he was exposed to. Indeed, I have never forgotten him from that day.”

The Cintra Convention was signed on 31 August 1808 and three generals, including Wellesley, who had disagreed with the terms but was over-ruled, were recalled to London to explain themselves. Command of the army in Portugal fell to General Sir John Moore, and with him Hill and his men marched into Spain. By December it was apparent that Napoleon himself had come to take command of the French army in order to drive the British into the sea. Thus began the headlong retreat through the mountains of north-west Spain to Corunna in appalling conditions of rain, cold and hunger. During this time Hill received news, at Lugo, that his uncle, Sir Richard Hill of Hawkstone in Shropshire, had died and left him £2000 and the estate of Hardwick near Hadnall, about 5 miles north of Shrewsbury. Hill scribbled his will quickly; survival at that moment was uncertain. Napoleon returned to Paris on 1 January 1809, leaving Marshal Soult to continue the pursuit of the British army. In the battle of Corunna on 16 January Moore was killed, and Hill’s men held off the French on the left flank of the British army. Embarkation was successfully completed on 17 January, and the army conveyed back to Plymouth. The soldiers were in poor shape, dirty, hungry and ragged. Hill had done what he could to care for his men during the whole campaign, both in the heat of summer and in the harsh winter, and was already being called by them Daddy Hill.

By April 1809, Hill was back in Portugal, and played a significant role in the battle of Oporto (aka the Douro) in May when Soult’s army was expelled once more from Portugal. Following the French into Spain Wellesley won the battle of Talavera, west of Madrid, where Napoleon’s brother Joseph was residing as King of Spain. Hill was almost captured in the early stages of this battle, which was fought over an evening and the next day, 27/28 July 1809. It was during this battle that his staff heard Hill swear – one of only two occasions. He was a Christian man and took his faith seriously. After the battle Hill wrote to his sister Maria at Hawkstone “ dear-bought… another such victory would be a serious one for us”. The French armies greatly out-numbered the British and their allies.

Despite the victory, the army, short of provisions, withdrew into Portugal, where many soldiers succumbed to fever. During the autumn of that year, when not attending to his duties, Hill organised hunting for his officers with hounds sent out from Hawkstone, and bought local sheep to send to Hawkstone to improve the local breed.

At this time he was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant- General, and in December was offered a semi-independent command of part of Wellington’s army (Wellesley had been given the title Viscount Wellington after the battle of Talavera). This offer clearly demonstrated the trust that Wellington was willing to place in Hill. They had known one another for some years, and were both friends and colleagues. Hill invariably followed all orders he received with the utmost care, and Wellington said of him “The best of Hill is that I always know where to find him”.

The reason for this separate command was that while Wellington’s main force was operating on the north eastern frontier of Portugal and Spain, opposed by the French armies of Portugal, the Centre (based on Madrid) and the North, Hill was to guard Wellington’s south flank from possible attack by Marshal Soult commanding the French army of the South. Hill therefore found himself manoeuvring in and out of Spain along the mid to south frontier of Portugal.

Most of the year 1810 was devoted to training Portuguese troops, who turned out to be reliable and courageous fighters. In the autumn of that year Wellington began a withdrawal from the frontier back into Portugal, pursued by Marshal Masséna. Wellington enforced a scorched earth policy and, as the army withdrew south-westwards into Portugal the Portuguese civilian population followed. At Busaco on 27 September Wellington, with his army strategically positioned on ridges above steep slopes and Hills’ Second Division on his right flank, held Masséna at bay, and then continued his withdrawal to the famous Lines of Torres Vedras. This was a strongly fortified area north of Lisbon, constructed over the preceding year in complete secrecy, in which the British and Portuguese troops could winter in safety, well provisioned from British ships in Lisbon Harbour. For about one month the French tested the lines for a possible attack, but on 14 November began a retreat back towards Spain through Portuguese countryside in winter, bereft of provisions – a disastrous situation for an army that lived off the land. Meanwhile, the British could enjoy chasing foxes with their hounds, comfortably encamped and well nourished.

At this time Hill succumbed to fever and, despite care in Lisbon, failed to recover and in January 1811 was sent back to Hawkstone to convalesce. Eager to return to his command, Hill sailed from Portsmouth in mid-May, just before the bloody battle of Albuera was fought under Beresford’s command of the Second Division (during Hill’s absence). Hill arrived at Wellington’s headquarters on 24 May.

The rest of the summer of 1811 was engaged in rebuilding the morale of the army after Albuera, and kin periods of serious manoeuvering to gauge French Intentions. At other times, when the French had withdrawn, the soldiers played football, and Hill often staged theatricals before dining his officers, enjoying the proceedings, his face looking like that of a contented farmer. Suddenly, in October 1811, all was to change.

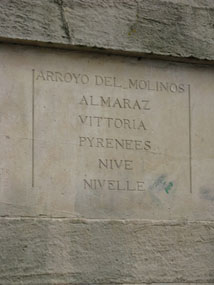

At the top of the centre column of a plaque on the plinth of Lord Hill’s Column in Shrewsbury is inscribed the name ARROYO DEL MOLINOS. This village in Spain was the scene of a sensational victory at the end of a relatively uneventful year.

General Girard had led a division of the French Army of the South to a relatively northerly part of its region to occupy the town of Caceres. The 6,000 soldiers involved were thus isolated, and Hill proposed to Wellington that an expedition be mounted against this division before it could move south or be re-inforced from Soult’s main army. Wellington approved, cautioning against Hill over-extending his lines and generally recommending that Hill push Girard’s division southwards without risking a battle. In atrociously wet weather, Hill urged his men forward by forced marches through mountainous country towards the French, who were by this time moving slowly south by the main roads. Hill took short cuts by mountain tracks and on 27 October arrived within three miles of Arroyo del Molinos, where the French planned to rest for the night. Hill urged his soldiers forward on a forced march over several d Starting at 0200 in the morning of 28 October in a storm of hail, Hill’s men moved forward to the edge of Arroyo, and at daybreak, as the weather cleared, broke into the village. The French were caught by surprise, and although Girard escaped, General Brun was captured, as was the Prince d’Aremberg, a member of Napoleon’s family circle by marriage. This was a coup in itself, and the prince was eventually sent to Shropshire for the period of his captivity, and stayed between Oswestry and Whitchurch. Over 1300 French prisoners were taken. Hill’s casualties were in total less than 100, with only seven men killed. At the end of a quiet year with little excitement, news of this victory caused great delight in England. Wellington requested of Lord Liverpool, secretary of state for war, that the Prince Regent should bestow some mark of favour on Hill; “his services have been always meritorious and very distinguished in this country, and he is beloved by the whole army…”. The result was that Rowland Hill was made a Knight of the Bath, becoming Lieutenant-General Sir Rowland Hill KB. In late November the Shrewsbury Chronicle invited its readers to rejoice over this “very brilliant achievement”. The people of Shropshire were evidently becoming more aware of events in the far-off Peninsula. No doubt Rowland Hill’s period of convalescence earlier that year had been a time of many dinners and much conversation about the conduct of the war. Hill had also become a person of consequence on account of his inheritance of Hardwick.

The first months of 1812 saw Wellington finally capturing the strategically important towns of Ciudad Rodrigo (in January) and Badajoz (April). Hill’s division played an important part in occupying Spanish towns east of Badajoz to prevent Soult’s Army of the South from moving up to harry Wellington’s army. Following these bloody but (for the British and their allies) successful sieges French army activity became intense with units crossing the river Tagus by way of pontoon bridges at Almaraz in order to move reinforcements from south to north and vice versa. Wellington ordered Hill to capture this crossing and the forts nearby which guarded it.

Hill, as usual, sent parties to reconnoitre the ground and, choosing a moment when there were few French forces in the region, advanced by forced marches over mountain roads in order to fall upon the French position. An attack (on 16 May) on the strongest fortress, the Castle at Mirabete, was unsuccessful and subsequently deemed unwise on account of uts strength. Hill paused to reconsider his options and on the night of 18 May led his men over a steep mountain track which led to a position not more than half a mile from Fort Napoleon guarding the southern approach to the bridge. The date was 19 May. While part of his force mounted a feint against Mirabete, Hill ordered an attack on Fort Napoleon, which fell after a fierce struggle lasting less than an hour. Having captured Fort Napoleon, Hill’s men rushed over the bridge and captured the fort on the northern bank of the Tagus, which the French had abandoned. Hill, now in command of the river crossing, captured a huge amount of stores and arms, most of which had to be destroyed for lack of men and animals to transport it. Once again, by careful preparation, Hill ‘the surpriser’ had won a significant victory over the French, who shortly afterwards abandoned the castle at Mirabete as Almaraz had ceased to be of any advantage to them. The operation greatly hindered the movements of the French armies of Portugal, the Centre and the South in their attempts to collaborate, forcing them to make all river crossings further to the east and so further from where Wellington was manoeuvring.

After Wellington’s significant victory at Salamanca (the French and Spanish call the battle Arapiles)on 22 July, Hill, having been hard at work on the south flank watching the movements of divisions of the French Army of the South, moved north to be nearer Wellington, who briefly occupied Madrid, King Joseph having retired to the east coast at Valencia. Despite these morale-boosting victories the British withdrew from their somewhat exposed position and by the end of 1812 had endured another cold wet retreat into Portugal. As during the retreat to Corunna in 1808,once again, in these adverse circumstances, Hill received in November the encouraging news from Shropshire that he had been elected as one of the two Members of Parliament representing Shrewsbury.

This Coalport Election mug is shown by courtesy of Shropshire Museums Service, and would have been made either in support of or to celebrate Rowland’s successful candidacy, managed for him in his absence by his father Sir John, now residing at Hawkstone. The electors of Shrewsbury were clearly well aware by now that they had a local ‘hero’ to be proud of.

It was apparent in early 1813 that Wellington had recovered his spirits, which seemed to have been low at the end of 1812. Quietly, he arranged that instead of being provisioned from ships sailing from Britain into Lisbon harbour, necessitating long lines of communication behind him, he would take advantage of the capture of harbours on the north coast of Spain (the French having left north-west Spain) so that as he advanced north-east into Spain he would be marching towards his source of provisions of food and matériel along ever-shortening lines of communication. He also arranged for the difficult operation to be carried out of moving his pontoons from the River Tagus northwards to the River Douro. This took several weeks.

As winter turned to Spring, he made various movements to confuse the French armies as to his intentions. The French were greatly reduced in numbers, Napoleon having withdrawn thousands of troops to strengthen his armies in Germany following his retreat from Moscow in late 1812. As part of the British army, under Hill’s command, entered Salamanca, Wellington sent another contingent under General Graham north-eastwards through the mountainous district in north Portugal known as the Tras os Montes. The French never conceived of this mountainous area being passable and were consequently astonished to find that they had been outflanked to the north by Wellington’s forces which had crossed the Douro unopposed using the relocated pontoons. To avoid being cut off from their main route to the Pyrenees, and pursued by Wellington and Hill from Salamanca, the French army, burdened by vast quantities of loot and many Spanish who had sided with the French in Madrid and were now fearful of the consequences, struggled north-eastwards, abandoning one major town after another.

On 21 June, the armies met at Vitoria. Hill’s Corps was stationed on the right wing and held the ridge of La Puebla. Wellington commanded the centre and Graham the left. When the French realised that Graham was moving forward to cut off their line of retreat they fled northwards to the Pyrenees and the frontier with France abandoning all their booty. Joseph Bonaparte barely escaped capture, and fled back to France to face the wrath of his younger brother. The British soldiers fell on the spoils, chiefly gold and drink, with the result that the French were not pursued in a manner which might have shortened hostilities. The soldiers were exhausted and inebriated. The hundreds of paintings in Joseph Bonaparte’s baggage train, looted from Spanish palaces, museums and houses, ended up in the safe-keeping of Wellington. After the war, he offered to return them to their rightful owner, the restored Spanish King Ferdinand, but he refused to accept them, conferring them on Wellington as a gift in gratitude for his services in assisting in the liberation of Spain. They now hang in Apsley House (“Number One, Piccadilly”).

Throughout the summer and autumn of 1813, Wellington slowly made his way north onto the French frontier, opposed by Marshal Soult who had been sent by Napoleon to reorganise and revive the morale of the defeated French Armies of Spain. These troops were now fighting to defend their homeland.

On 7 October the British entered France on the extreme west of the frontier at Fuenterrabia and Hendaye. Ten days later Napoleon was defeated at Leipzig after a three day battle against the combined forces of Austria, Prussia and Russia. This news, when it reached the Pyrenean frontier, gave great encouragement to Wellington and his allies. On 10 November they forced a passage across the River Nivelle, following this with a further crossing of the Nive on 10 December. Hill’s Corps was deeply involved in both these battles, but his greatest success followed on 13 December when he fought against superior odds at St Pierre in a position isolated by the breaking of a pontoon bridge. Single-handed, and in face of weaknesses and treachery by some of his subordinates, Hill managed to hold his force together until, at about 1400, realising that the pontoon bridge had been repaired and that Wellington was sending reinforcements, Hill seized the initiative and led his men forward against the French. By the time Wellington arrived on the field of battle, the crisis was over and Wellington could salute Hill with the words “Hill, this victory is all your own!”. Less happily, Wellington did not subsequently give adequate credit to Hill for this victory in his despatches to London. For this reticence on Wellington’s part Hill’s triumph is less well known than it deserves to be. Even on the plaque on his Column there is mention of Pyrenees, Nivelle, Nive and Hillette, but not St Pierre by name. It was during the critical situation when a colonel deserted the front line and moved to the rear that Hill was heard to swear for only the second time during the entire war! Wellington was heard to remark later, when told of this “If Hill is beginning to swear we had better get out of the way”.

More happily, even as Hill’s men rested after this fiercely fought battle, most interesting developments were taking place in Shrewsbury. On Friday 17 December 1813, The SHREWSBURY CHRONICLE announced a momentous “ PROPOSAL for CELEBRATING in SHREWSBURY the LATE VICTORIES obtained by the BRITISH and ALLIED ARMIES.”

The report indicates that the editor was well aware that with the improvement in trade resulting from these victories “the population of almost every City and Borough have manifested their delight by illuminations and conviviality, and have sent up Congratulatory Addresses to the Throne.”

Shropshire then (perhaps as now!) was not demonstrative, as the continuing report suggests:

“The inhabitants of Shrewsbury, not less susceptible than those of any town of the feelings of genuine patriotism, have not, it is true, on the present occasion, evinced those feelings by any noisy rejoicings: But who did not see the delighted countenances of all ranks hailing the nightly arrivals of the decorated mail coach? Who did not witness persons in the higher sphere affably communicating the tidings to their not less anxious but more humble neighbours? In short, the rich and the poor, in fulness of heart, congratulated each other, and the whole town wore the appearance of happiness and holiday.

“It is nevertheless submitted, whether, in conformity with national custom, the town of Shrewsbury ought not to proclaim its joy in some public manner: – not by illuminations or fireworks, or convivial meetings, or toasts or songs; but by some act which will remain permanent – permanent as, it is hoped, the beneficial result of our successes will prove to us and other nations.”

It does appear that this initial suggestion came from the Shrewsbury Chronicle, whose editor reminded his readers of the “many natives of this county who have bravely fallen, and still how many bravely stand among the ranks of those armies which have fought their way, battle after battle, over the territories of Portugal and Spain into the dominions of France! How many of our neighbouring families have sons or other relatives who are officers there! How often has the Native of Shropshire, the Representative of this Borough – GENERAL HILL – how long has his skill contributed, in one quarter at least, to uphold the spirit and independence of Nations – to defeat invasion – and to bring about the period on which we are now congratulating each other. Have we, then, no token of esteem and applause to bestow upon General Hill?

The writer drew attention to monuments being prepared in other places for local heroes – Graham in Scotland, Picton in Wales and Marquis Wellington (as he had now become) in Dublin. He was anxious lest Plymouth (of which Rowland Hill was Governor) should “snatch from us an honour, by ‘adopting’ him as their own”. He suggested possible sites for a COLUMN or other such memorial, and, having stated that this issue was above ‘Party’, went on to address the reaction of “those persons who object to War in general”. They cannot “ feel reluctant to express their approbation of the character of one whose humanity is, if possible, a more conspicuous trait than his valour”. He quoted from an article by The Revd Archdeacon Corbet in the Chronicle of 9 October 1812, referring to Hill’s “firmest intrepidity combined with the strictest attention to human suffering”.

Finally, the writer addressed the possibility that it might “be objected that the present proposal is not likely to succeed, because it does not originate in a higher quarter “. Against this possibility he argued “the circumstance of its emanating spontaneously from the people will render the offering more acceptable to such a character as Sir Rowland”.

A Book was to be opened at the Printer’s, to avoid any loss of time, and a meeting would be called.

One week later, on Christmas Eve, the Chronicle announced that a meeting would be held to discuss the proposal to erect some memorial and that “subscriptions for this purpose already amount to several hundred pounds”.

At the public meeting held on 30 December it was resolved that a memorial should be erected. By the following October it was clear that the monument was indeed to be a COLUMN , that £3,949 had been subscribed and that upwards to £1500 was still required. The foundation stone was laid on the Feast of St John the Evangelist, 27 December 1814 by “the Salopian Lodge of free and accepted Masons ”.

Meanwhile, in the first three months of 1814, Napoleon had been forced back to Paris by the combined forces of Austria, Prussia and Russia despite his fighting superb delaying battles in Belgium and north-eastern France, and in the south Wellington and his colleagues had forced Soult slowly across one river after another, with actions at Orthes, Tarbes and finally Toulouse.

The battle for Toulouse was in fact an unnecessary tragedy, being fought on Easter Sunday, 10 April. The news that Napoleon had abdicated on 6 April had not reached the south when the allies battled their way into the city and Soult retreated south-east, followed by Hill. Only on 17 April did Soult accept the fact and capitulate.

One of the features of the campaign in these last months of fighting was the welcome which the allies received. Bordeaux declared for the allies on 12 March as did the Mayor of Toulouse after the battle. The French were by this time exhausted by war, hating conscription and increasingly impoverished by taxes and lack of trade.

Wellington entered Toulouse on 12 April to an ecstatic welcome. He gave a Ball in the Préfecture in the evening where white cockades were worn to celebrate the restoration of the Bourbons in the person of Louis XVIII.

Hill returned to Shropshire on 23 June 1814. On 30 June he was welcomed into Shrewsbury in a Triumphal Procession from Coton Hill, ending at the Lion Hotel. Lord Hill – he had been created Baron Hill of Almaraz and Hawkstone with a pension of £2,000 a year – then went to the Guildhall where a splendid dinner was served. The decorations included a flag bearing the motto “Long life and success to the Hawkstone Lads” – a delightfully democratic tribute to Rowland and his military brothers Robert, Clement, Noel and Edward. His eldest brother John had died earlier in 1814 at Hawkstone. He was buried at Hodnet.

Because he had been in the Peninsula Rowland never entered the House of Commons. On his elevation to the peerage he entered the House of Lords in June 1814.

Celebrations of the Hero and his brothers continued for weeks afterwards, with visits to villages, dinners, balls and ox roasts for the poor, presentations etc.

As the lower stages of the Column emerged above ground in 1815, we can only imagine the consternation felt when the news broke that Napoleon had left Elba and was back in Paris. Hill had gone to London with his sister Emma, and lost no time in travelling to Brussels, arriving on 1 April. Wellington hastened thither from Vienna where the Congress was in progress, arriving on 4 April.

On 18 June the final battle of the Napoleonic wars was fought at Waterloo. Hill was given the task of guarding Wellington’s right flank and keeping open the route to Antwerp should the British army be forced to retreat. Late that day, as Blϋcher’s Prussians marched onto the battlefield, threatening Napoleon’s right flank, Napoleon sent in the Old Guard against Wellington’s position in the centre. Hill and others moved against the left flank of the Guards as they advanced in column against the British squares, and devastated their ranks with their fire. The Guard halted and recoiled. The French began to shout “La Garde recule!” Then it dawned on the French soldiers that it was the Prussian army and not Grouchy’s troops, as Napoleon had lied to them, moving towards their right, and with cries of “Nous sommes trahis!” and “Sauve qui peut!” they fled from the field.

Work on the Column continued as Napoleon sailed to St Helena on a British ship and on 18 June 1816, the first anniversary of the great battle, the Column was completed, and the statue of Lord Hill placed on top. It was made of Coade artificial stone and, at 17 feet, was one of the largest, if not the largest statues ever made at the Coade Stone Works near the site of the Royal Festival Hall in London. It cost £315 – a very large sum in those days.

From 1828, when Wellington had to relinquish the post of Commander-in-Chief of the British Army on becoming Prime Minister, Lord Hill succeeded him and held the post until 1842. In that year he was created a Viscount, and granted the privilege that the title could be inherited by his nephew, as Lord Hill never married and so had no direct heir. He died at Hardwick on 10 December 1842 and lies buried in Hadnall church where a memorial to him on the north wall of the nave bears a figure of a shepherd and a soldier. It seems to express the essence of the man – his humility and his humanity.

If you have enjoyed reading this account of the man whose statue stands at the top of Shropshire’s column, please help to have a new statue made in coade artificial stone – a very hard-wearing medium – so that his achievements and his character can continue to be appreciated by Shropshire people and all who visit their beautiful county. Why not become a Friend for a Fiver of Lord Hill’s Column and have a hand in saving it!